Paul Revere Williams in Northern and Central Nevada

Alicia Barber, PhD

Intro

To explore the work of Paul Revere Williams in northern and central Nevada is not only to gain insight into the remarkable breadth of his creative range, but to open a window into a transformational era in the state’s history. Spanning the 1930s and 1940s, Williams’ work in the region is deeply intertwined with the growth of its distinctive culture and economy, including its longstanding industries of ranching and mining and its development into a divorce capital, tax haven, and national tourist destination.

Brought to the state by three of its newest—and wealthiest—arrivals, Williams made permanent contributions to the landscape of northern and central Nevada through confirmed projects that include four private residences, a cluster of manufactured steel homes, an elegant Neoclassical Revival church, and a charming motor lodge, plus designs for an unbuilt rehabilitation center.

Click to Download PDF Version

The Luella Garvey House (1934)

Williams’ first Nevada commission, in 1934, accompanied a notable period of in-migration to Nevada during the Great Depression. The client was Luella Rhodes Garvey, a 60-year-old woman of substantial wealth—at her death in 1942, her estate was worth $3.5 million, the largest ever to be filed in Nevada, and the equivalent of $60 million in today’s dollars. She and her first husband, steel magnate Clayton Garvey, had lived in Pasadena, California until his death in 1925. Less than a year later, she married a man named William Schupp (one account called him a “cowboy”) but the match did not take. In 1927, Garvey arrived in Reno to file for divorce. In doing so, she took advantage of the state’s unique statutes enabling the dissolution of a marriage after one spouse had resided in the state for just three months (shortened to six weeks in 1931).

As sometimes happened with new divorcées, Garvey did not leave Nevada for good after receiving her decree, instead splitting her time between Los Angeles and Reno for the next few years. One reason was likely financial; Nevada was quickly gaining a reputation as a tax haven for the affluent, boasting no state income tax, no inheritance tax, and no corporation tax. This array of enticements would be packaged just a few years later into the “One Sound State” promotional campaign initiated by Reno’s First National Bank, which mailed pamphlets directly to thousands of wealthy prospects, urging them to relocate to Nevada.

The effort was largely successful. Lured by the state’s fiscal benefits, millionaires including Max C. Fleischmann, Wilbur D. May, and LaVere Redfield established residences in Nevada in the 1930s, with many also retaining homes elsewhere, an arrangement particularly appealing to wealthy Californians. Although few brought new businesses with them, many would leave behind bequests and charitable foundations that enabled the establishment, construction, and expansion of institutions, schools, churches, services, and nonprofits, with an impact that continues to this day.

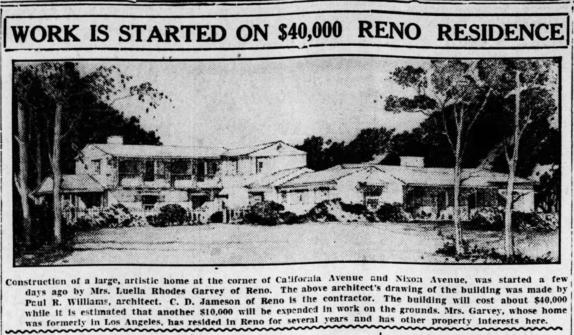

Luella Garvey hired Williams in 1934 to design a house for her on the corner of California and Nixon Avenues, just east of the row of lavish mansions adorning Reno’s Newlands Heights. Precisely how Garvey came to hire him is unknown, but her interest in doing so is not surprising. Just shy of forty, Williams already enjoyed a national reputation and was in great demand as an architect of private residences for wealthy and prominent clients throughout the Los Angeles area. His cachet had grown exponentially after being hired by automobile magnate Errett Lobban “E.L.” Cord in 1931 to design Paul Revere Williams in Northern and Central Nevada his 32,000 square-foot mansion in Beverly Hills, known as Cordhaven. Luella Garvey may even personally have known some of Williams’ prior clients, several of whom lived near her home in Pasadena.

By the mid-1930s, Williams clearly had transcended many of the professional impediments imposed by racial prejudice, at least in southern California. And because Garvey spent a lot of time there as well, it is possible that they made most of their arrangements outside Nevada. It is unclear what kind of a reception he might have received in Reno, where African Americans comprised less than one percent of the county’s population. There are secondhand reports that he had some trouble being accepted by local contractors, all of whom were most likely white. Reno in 1930 was a town of 18,529 residents, only 123 of whom were Black. Racial discrimination was increasingly embedded in the city’s housing market, where racially restrictive covenants were imposed upon many of the subdivisions established after the mid-1920s—covenants that explicitly prohibited any non-white residents from either purchasing or renting homes in them.

Although Williams designed many houses in restricted neighborhoods elsewhere, the Reno tract of Rio Vista Heights, where Garvey had purchased her property, was not one of them. In any case, the combination of her wealth and Williams’ renown would have limited the power of any racial prejudice to impact their plans. Hiring Williams was a largely private arrangement, since architects did not need licenses to practice in Nevada until the state legislature created the State Board of Architecture in 1949.

Williams was therefore free to work for anyone in Nevada who could afford to hire him, and there is every indication that his Nevada clients were keenly aware of his star power. His name accompanied a drawing of Garvey’s “large, artistic home” that appeared in the Reno Evening Gazette as construction got underway in June of 1934. At a cost of $40,000 with an additional $10,000 budgeted for landscaping alone, the home was staggeringly expensive for a private residence in Reno, especially during the Great Depression.

Stylistically, the Garvey house shares features with many Williams had designed in California; its combination of Colonial Revival elements with Georgian and French Regency influences was becoming a Williams signature. The house is strikingly similar to one he had designed in 1933 for Paul Revere Williams in Northern and Central Nevada. Seth and Dorothy Hart in Holmby Hills, just west of Beverly Hills. Both are white brick, with a New Orleans-style second-floor balcony featuring identical foliated wrought iron detailing. It was an eclectic style that Williams proudly connected to his racial heritage. In an interview for the Baltimore Afro-American in December 1935, he expressed his deep satisfaction in having made “New Orleans Colonial architecture” fashionable in southern California, stating “Frequently, now people pass by houses of White architects to point out the New Orleans mansion being built by a colored architect.”

The house’s delicate ornamental iron work was said to have been cast locally by Andrew Ginocchio of Reno Iron Works, who continued to work with Williams on his other local projects. The house was Lshaped, with sixteen rooms and an interior courtyard and patio, and together with its landscaped grounds filled three city lots. Living there without any relatives, Garvey had it designed as a duplex, occupying the front portion while her attorney and friend, Edward Lunsford, rented the back. A rear wing housed her servants. Garvey resided there for the remaining eight years of her life, and the house was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.

The Luella Garvey House Figures

Figure 1 – The Reno Evening Gazette published a drawing of the Luella Garvey House on June 23, 1934 as construction began.The Herman House at Rancho San Rafael (1936)

Approximately a year after Luella Garvey’s home was completed, Williams was hired to design the Reno residence of another group of wealthy southern California transplants: Dr. Raphael Herman, his brother Norman B. Herman, and Norman’s wife, Mariana. In January of 1936, the Hermans jointly purchased the Russell Jensen ranch, which sat on more than 300 acres just northwest of the University of Nevada campus, right outside city limits. The ranch had been established by the Pincolini family in the 1890s for running cattle. Upon taking ownership, the new owners gave the property the romantic name of Rancho San Rafael (using the Spanish variant of Raphael).

All three Hermans were immigrants: the two brothers from Germany and Mariana from an area of Austria-Hungary now defined as Croatia. Raphael was perhaps the best known of the three. A manufacturing executive and philanthropist, he was the donor of a $25,000 world peace prize first bestowed upon Stanford University chancellor emeritus Dr. David Starr Jordan in 1924. Although sometimes incorrectly referred to as a physician, Dr. Herman gained his title through an honorary doctorate from the University of Southern California. His brother, Norman B. Herman, was a manufacturer and prominent real estate broker in Los Angeles, and had married Mariana—an aspiring actress who had appeared in several silent films—in 1927.

It is not clear if the Hermans knew Luella Garvey personally. Mariana Los Angeles Times Photographic recollected years later Nevada’s gorgeous blue skies, experienced on a sightseeing trip through the state, had that inspired the three to purchase property with it as well.

Being in the real estate business in Beverly Hills and Hollywood, Norman B. Herman very likely had prior contact with Paul R. Williams, and is named as the client on the plans Williams completed in February 1936 for the spacious residence the Hermans would share when staying at the ranch. The house’s wood construction lent a more rustic feel to its Classical Revival style. Built for comfort as well as entertaining, it had eighteen rooms and a beautiful outdoor patio and courtyard featuring a built-in brick cooking area reportedly designed by Andrew Ginocchio.

Designing houses for ranch properties wasn’t new to Williams. Some of his southern California clients at the time owned sizable acreage they called “ranches” on the periphery of Los Angeles, where they hired Williams to design homes that ranged from modest to luxurious. In Reno, many wealthy new arrivals from urban areas found the prospect of ranch ownership appealing. Some ran their properties as commercial operations, as Wilbur D. May did by raising thoroughbreds at his Double Diamond ranch south of Reno (the two diamonds of his ranch’s name were formed from stacking his initials, W and M).

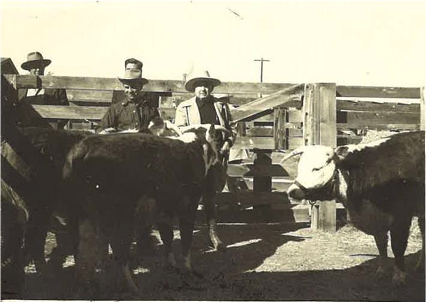

Rancho San Rafael continued to function as a working ranch under the Hermans, who hired local couple Joe and Grace Callahan to manage the property and its operations. There, they grew produce and hay, and raised chickens, rabbits, turkeys, and registered prize cattle. But it was clearly a recreational property as well. The cattle watering pond was stocked with fish and a variety of quail, pheasants, and other game were introduced to the ranch for the hunting and fishing enjoyment of the Hermans and their guests.

All three Hermans continued to split their time between Reno and Beverly Hills, allowing them to take advantage of Nevada’s tax benefits without relinquishing their California ties. When they did travel to Reno, often for months at a time, they brought a full array of staff, which for Dr. Herman generally included a bookkeeper, housekeeper, chauffeur-butler, cook, and secretary.

Raphael Herman died in 1946 followed by his brother Norman in 1960. In 1964, Mariana Herman offered to sell the expanded 400+ acre ranch to the University of Nevada, suggesting that the main house, designed by such a prestigious architect, would make an ideal home for the university’s president, but the university could not meet her price or terms. A decade later, local community members suggested the land be used for a regional park. Through their efforts, the ranch was purchased in 1979 by the state’s Public Employees Retirement System and then sold to Washoe County, which now operates it as San Rafael Regional Park and rents out the main house for special events and gatherings.

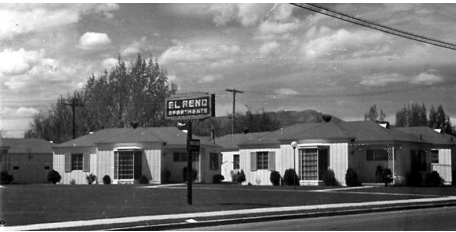

The El Reno Apartments (1937)

The next appearance of a Williams design in Reno was a major departure from the previous two, and reveals a completely different side of his body of work. Although Williams designed grand homes, as well as hotels, churches, hospitals, schools, and other imposing edifices, he maintained a lifelong interest in small houses, and had been entering small house design competitions since 1923.

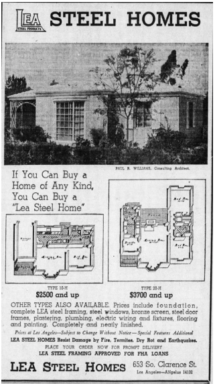

In the mid-1930s, the opportunity arose for Williams to promote well-designed smaller houses that were made even more affordable through the use of innovative and efficient construction techniques. LEA Steel Homes, a company based in Los Angeles, had developed a method to prefabricate modular housing components from sheets of galvanized steel, to be easily assembled on site with patented bolted connections that required no welding.

Williams became a consulting architect for the company and designed a steel house for the 1936 California House and Garden Exhibition, sponsored by the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce and the Federal Housing Administration. The modular homes promised resistance to damage caused by fire, termites, dry rot, and earthquakes. They were offered for prices starting at $2500, which included the foundation, complete steel framing, steel windows, bronze screens, steel door frames, plastering, plumbing, electric wiring and fixtures, flooring, and painting. Williams designed the little houses to resemble traditional construction, with the exterior metal siding imprinted with a faux wood grain. They also featured his trademark ornamental ironwork around the entryway.

Reno resident Roland Giroux decided that the prefabricated steel homes could make excellent rental properties and arranged for fifteen of them to be erected on eight lots he had acquired in 1936 on South Virginia Road between Pueblo and Arroyo Streets, just past city limits on the southern edge of town. Giroux had a pedigree that spanned California and Nevada; the son of Nevada mining magnate Joseph L. Giroux, Roland had grown up in Los Angeles, where he operated a wholesale photography supply business in the 1920s. Once he had purchased the lots in Reno, a team of local contractors set to work arranging and equipping seven of the steel houses to face South Virginia, with two rows of four facing north and south.

From the time they opened in August 1937, the charming little “individual apartment homes,” as Giroux called them, enjoyed a brisk business, popular among both divorce-seekers and permanent residents, including—for short periods in the 1940s—such luminaries as Bill Harrah and Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. But the little community was not to last. According to one account, the City’s rent control board refused to let Giroux raise the rents (even though the tenants were willing to pay more) and he decided to cut his losses and sell off the houses individually. Most remained in town; of the original fifteen, twelve have been identified at various locations in Reno, and one is listed on the City of Reno historic register. A Sewell’s Supermarket, since converted into Statewide Lighting, was built on their original South Virginia Street site in 1959.

El Reno Apartments Figures

Figure 9 – An advertisement for LEA Steel Homes published in the Los Angeles Times, July 12, 1936The First Church of Christ, Scientist (1939)

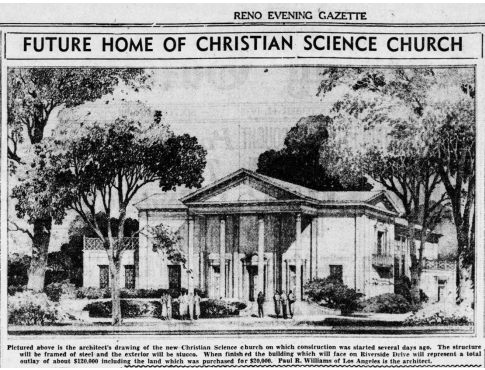

Williams returned to Reno in 1938 for another project connected to his former client Luella Garvey and designed what many consider his crowning achievement in the region: the First Church of Christ, Scientist. Garvey had become interested in the congregation’s plans to construct a new building, and in January 1937, contributed $15,000 to the cause. Her generosity continued with a second donation of $25,500 that enabled them to purchase their desired site, a choice parcel on tree-lined Riverside Drive, which stretches peacefully along the north bank of the Truckee River on the west side of downtown.

Williams was not simply handed the commission; he had to compete for it. And the congregation had strong ideas about what they wanted. For inspiration, Anna Frandsen Loomis, chairperson of the church’s building committee, consulted the teachings of the religion’s founder, Mary Baker Eddy, as well as biblical accounts of Solomon’s Temple. Four architects attended the committee’s meetings to offer sketches and participate in discussions. In addition to Williams, they included Gwynn Officer of Berkeley, California, and two highly regarded Reno architects, Russell Mills and Lehman Ferris.

On April 19, 1938, the building committee unanimously selected Williams, who submitted his initial plans on May 2. Walker Boudwin was hired as general contractor, and the project broke ground on September 22. Although unconfirmed, relatives of ironworker Andrew Ginocchio, who again worked on Williams’ local team, have reported that for the duration of the project, which took about a year, Williams retained a small office in the home of Ethel Zimmer at 529 West First Street, just across from the job site (the house is no longer standing).

The elegantly serene Neoclassical Revival church opened to the public on October 22, 1939, having cost around $140,000. The interior features several Williams signatures—large windows on the east and west walls that bathe the nave in natural light, and an encompassing attention to detail, expressed perhaps most charmingly in the wire hat racks found on the underside of each of the approximately 600 seats. Separate rooms offered space for childcare, readers, and singers, as well as lodging for the building’s caretaker, with Sunday school classes held in the basement.

Upon her death in 1942, Luella Garvey left the congregation a trust fund of $100,000 to support the building’s maintenance. By the time the congregation moved to a new building in 1998, discussions had been underway for many years to convert the church into a theater. A $1.1 million donation from Moya Lear gave the plan legs and the building a new name: the Lear Theater. However, the theater project languished after many years, and the building, which is listed on the City and State historic registers as well as the National Register of Historic Places, was donated by Lear Theater Inc. in 2011 to the local nonprofit arts organization Artown, which sold it to the City of Reno in the fall of 2021.

First Church of Christ, Scientist Figures

Figure 12 - Anna Frandsen Loomis on the steps of the First Church of Christ, Scientist in 1942. Courtesy of Just Loomis.Rehabilitation Center, Steamboat Springs (unbuilt, drawings dated 1943)

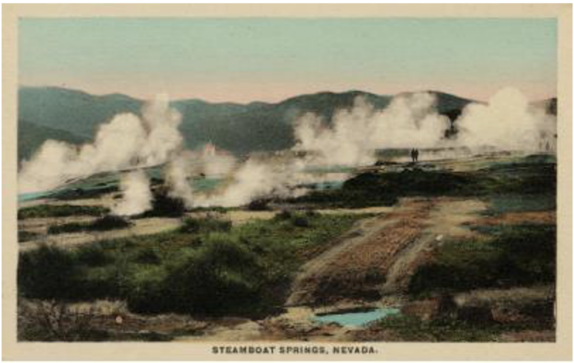

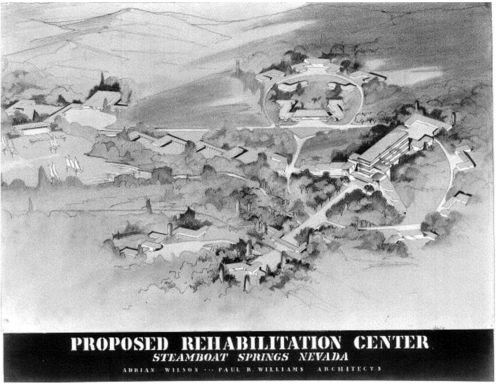

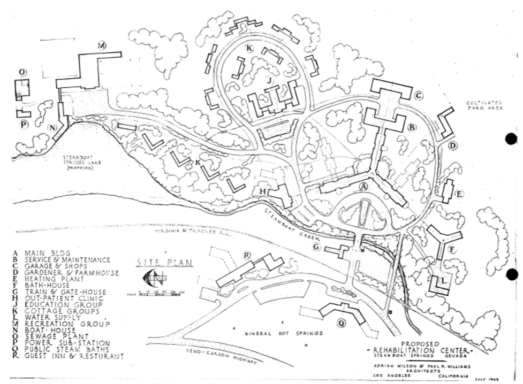

In 1942, Williams partnered with a frequent collaborator, fellow Los Angeles-based architect Adrian Wilson, on a series of drawings for a proposed Rehabilitation Center at the Steamboat Hot Springs, south of Reno. The project itself was entirely speculative, possibly connected to a larger effort to secure major financing to develop the springs into a world-class resort.

The geothermal springs had been the site of various sanitariums, hospitals, and accommodations since 1861, with its highly mineralized waters and mud lauded for a myriad of health benefits. Since 1918, the property had been owned and operated by osteopath Dr. Edna Carver, who constructed the Pioneer State Health Hotel there in 1925. The resort was a popular destination through the 1930s, even serving as a training camp for boxers Paulino Uzcudun and King Levinsky as they prepared for their fights with Max Baer in Reno. The hotel burned down in a huge blaze in 1937 and Carver proceeded to rebuild it.

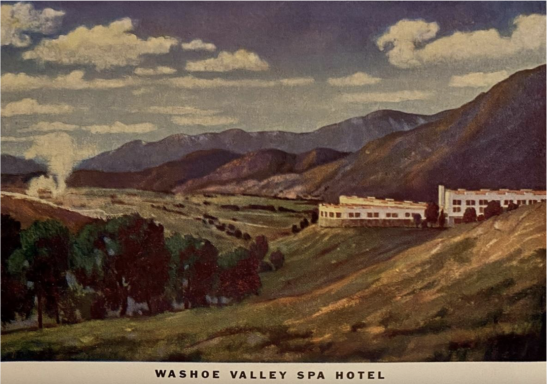

In 1941, the Reno Chamber of Commerce proposed developing and expanding the resort into a major health spa, and Dr. Carver wrote up a formal prospectus for a “Washoe Valley Spa at Steamboat Springs” touting the site’s accessible location, its proximity to recreational amenities, including hunting, fishing, and skiing, and a list of ailments that the springs ostensibly could help alleviate, from arthritis to drug addiction. With wide-open gambling legalized in Nevada a decade earlier, the prospectus suggested the establishment of a casino on site, along with a restaurant and hotel, potentially featuring Spanish-style architecture.

It is not clear whether Williams and Wilson produced their drawings of a proposed “Rehabilitation Center” in direct response to Carver’s prospectus, or for completely different reasons. Their site plan, found in the archives of the American Institute of Architects by Stephen Keylon, depicts a sprawling campus including a fully-equipped, modern, multi-story rehabilitation center, groups of cottages, a bath house, educational and recreational buildings, an outpatient clinic, and a guest inn and restaurant—but no casino.

For whatever reason, perhaps the ongoing American engagement in World War II, the desired financing for a resort expansion never transpired, and Carver continued to operate Steamboat Springs in a fairly modest manner until her death in 1954, when it was inherited by her son and grandson. Interestingly, Williams and Wilson would later collaborate on the designs for a Communicable Diseases (CD) Building for the Los Angeles County General Hospital System and a related Respiratory Center at Rancho Los Amigos, both of which opened in 1955. The Steamboat Hot Springs remains operating under private ownership today and was listed in the Nevada Register of Historic Places in 1998.

Circle L Ranch House (1941)

The final stage of Williams’ involvement in north and central Nevada revolves around Errett Lobban (E. L.) Cord, the automobile magnate whose Beverly Hills mansion Williams had designed in 1931. In 1936, Cord began to purchase gold and silver mining properties in the Silver Peak District, in Nevada’s rural Esmeralda County, about seventy miles west of Tonopah. He continued to invest in the district after selling his Cord Corporation in 1937, and financed the construction of a large hangar and extended runway at the tiny Silver Peak airport in the spring of 1940 in order to accommodate the private plane he used to fly back and forth between Nevada and Los Angeles.

That June, Cord purchased the expansive Molini Ranch in the Fish Lake Valley west of Silver Peak, just outside the small community of Dyer, and named it the Circle L Ranch. His purchase of the working ranch, which comprised 2,200 acres and included 440 head of cattle, enabled Cord to establish his official state residency in Nevada, with all the tax advantages that conferred.

Cord immediately announced his intentions to replace or renovate the ranch’s existing buildings, and hired Williams to complete the designs. According to author Griffith Borgeson, Williams visited the ranch in the summer of 1940 and quickly produced plans for the entire compound, including the main house, barns, bunkhouse, warehouse and sheds. Coincidentally, the commission came around the same time that Williams was engaged in several other ranch projects for high-profile California clients, including the Breezy Top Ranch house for movie stars Richard Arlen and Jobyna Ralston and a residence for Lucy and Desi Arnaz on their Desilu Ranch.

The residence that Williams designed for Cord and his family bears a close resemblance to the Breezy Top Ranch house. It is both rustic and refined, a low-slung single-story white brick home with a knotty pine and brick interior, four large bedrooms and baths, a den with full bath, and a three-car garage.

Cord was said to have been extremely anxious about the prospect of a Japanese attack on the west coast, and moved his family to live on the Dyer ranch full time in 1942, stocking the house’s cellar and an adjacent warehouse with household staples. The two sons from his first marriage, Billy and Charles, already lived apart from the family, but the three daughters he shared with his second wife, Virginia (known as Gigi)—Sally, Nancy, and Susan—were all under the age of ten. A growth chart with the family’s names and heights remains on an interior doorway.

The family continued to vacation at the ranch for decades after the Cords moved back to Beverly Hills after the war and then to Reno, where they had a custom home built in the mid-1950s, and where Mrs. Cord often socialized with Mariana Herman when both were in town.

The Tharpe/Brinkerhoff House (1946) and Lovelock Inn (1949)

In the late 1940s, E.L Cord arranged for Williams to design two properties in the small town of Lovelock, Nevada, but not for Cord’s own benefit. Rather, the Lovelock Inn and neighboring residence were for the use of Cord’s brother-in-law, William A. Tharpe, and his family.

Tharpe was the brother of Cord’s second wife, Virginia, and their family was originally from Shreveport, Louisiana—as was William’s wife, the former Alice Lee Grosjean. In fact, Alice was a rather notorious figure back in their home state. In 1928, while still a teenager, she was hired by Governor Huey Long to be his private secretary, and soon became one of his closest and most trusted associates (and by some accounts, his mistress).

Long appointed Grosjean as Louisiana Secretary of State in 1930, when she was still in her twenties. In that capacity, she even served as governor of Louisiana for a single day in 1932 when Long’s successor, Governor Alvin O. King, was out of the state (there was no Lieutenant Governor at the time).

At the time of Grosjean’s marriage to William A. Tharpe in 1934, both were working for the Louisiana state government—Alice as Supervisor of Public Funds and William as Secretary of the State Tax Commission. Scandals and investigations swept through the highest levels of Louisiana state government for the next few years. Huey Long was assassinated in 1935, the Tharpes were both fired by Governor Richard W. Leche in 1939, and Alice was summoned to testify in a series of investigations related to various powerful figures. By 1941, the Tharpes had a daughter, Linda, and were running a motor lodge outside of Baton Rouge.

How the Tharpes spent the war years is unclear, but by 1946 they were living in Lovelock, Nevada, where Williams designed a house for them that September. Precisely why the Tharpes chose to move to Nevada is unknown, but their history suggests that they simply may have desired a fresh start. Proximity to family was clearly a factor. E.L. Cord continued to purchase additional property in rural Nevada, including a large ranch in Pershing County, near Lovelock, and another in Elko County, apparently naming all three the Circle L.

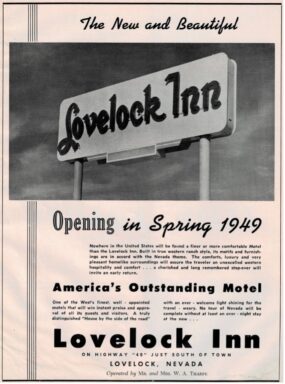

Having already operated a motor lodge in Louisiana, the Tharpes seem to have welcomed the prospect of opening one along busy U.S. 40—particularly one designed by Cord’s favored architect, the celebrated Paul R. Williams. Although the adjacent house was built first, its site was clearly chosen with the tourist lodgings in mind. The house itself is comfortable and spacious, featuring many of the same luxurious but rustic touches as the Circle L Ranch house, with knotty pine walls, vaulted wood ceilings, and stone fireplaces. Like the Herman house in Reno, it has a courtyard patio with a built-in cooking area.

By this time, Williams was well-practiced in the hospitality business, recognizing the need to create environments tailored to a lodging’s unique context and intended feel, as he had accomplished at the Mira Monte Hotel and Deep Well Guest Ranch in Palm Springs. The Lovelock Inn was built for $260,000 and opened in the spring of 1949 with thirty-three units. Built from Nevada stone mined near Carson City, its air-conditioned interior fully embraced the inspiration of the American West, with walls, ceilings, doors, and cornices of knotty pine, rock maple, and wormwood. A six-foot wrap-around covered porch provided shade and room to relax and enjoy the view, while a huge lobby and central fireplace offered indoor comfort in inclement weather. A teaser advertisement in Nevada Magazine in December of 1948 promised “The comforts, luxury and very pleasant homelike surroundings will assure the traveler an unexcelled western hospitality and comfort.”

Like everything else along U.S. 40, the Lovelock Inn was bypassed with the completion of Interstate 80, and the motel business took a hit. The Tharpes moved back to Shreveport in 1974, the same year that E.L. Cord died in Reno at age seventy-nine. Their Lovelock home was purchased by the local Brinkerhoff family, and the motel continued operating under separate ownership. After Alice died, in 1994, William moved to Reno to live with his sister, Virginia. Both Virginia and William died in 1995.

Spanning a period of just fifteen years, Paul Revere Williams’ designs for clients in northern and central Nevada embrace a wide range of settings and styles, demonstrating the remarkable versatility of a true master. Whether sited on a sprawling ranch, on the banks of a rushing river, alongside a ribbon of highway, or in the heart of a comfortable residential district, his contributions have become deeply embedded in the historical, cultural, and architectural fabric of the region.

The Tharpe/Brinkerhoff House Figures

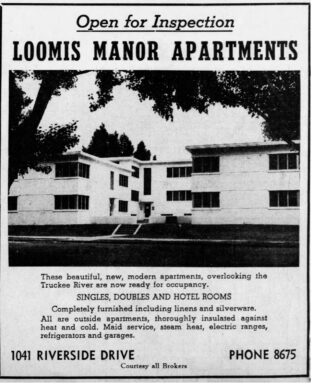

Figure 20 - Alice Grosjean Tharpe Weds William Allen Tharpe. St. Louis Star and Times, August 21, 1934ADDENDUM: The Loomis Manor Apartments (1939)

Not included in this list of confirmed Paul R. Williams designs is a building commonly attributed to him, the Loomis Manor apartments. Located just a few blocks west of the First Church of Christ, Scientist (the Lear Theater) on Riverside Drive in Reno, the Art Moderne building was under construction in 1939, at the same time as the church, for which Anna Frandsen Loomis chaired the Building Committee.

The claim that the apartment building was designed by Williams was first published by Christine Palmer in an article she wrote for the Nevada Historical Society Quarterly in 1993 after speaking with Anna Loomis’ grandson, Lynn Johnson. It has been repeated many times elsewhere, including on the Paul Revere Williams Project website and in other references to Williams’ work.

However, a close examination of the available evidence suggests otherwise. Although the absence of architectural drawings renders a final determination impossible, two factors seem to rule Williams out. One is the media coverage of the time. Although the apartment’s construction was featured in the local newspapers several times, none of the articles linked the building to Williams. That alone is curious, as he would likely have been hired for his cachet as well as his talents, and his name always appeared in print in association with the construction of the nearby church and, years earlier, with Luella Garvey’s house. What’s more, a lavish two-page spread accompanying the building’s grand opening in May of 1939 specifically attributed both the building’s design and construction to contractor Walker Boudwin.

While it may seem unlikely for a general contractor to also have designed the building, that’s where the second piece of evidence comes in. During this time period, Boudwin had under his employ a young architect named Edward Parsons, who would go on to become one of Reno’s most prolific and best-known architects. In his oral history for the University of Nevada Oral History Program, published in 1983, Parsons explained how he came to work for Boudwin in this period, essentially as a hired hand. With his original numbered job books in front of him as a reference, Parsons described the Loomis Manor Apartments as one of his projects, stating, “Number 13 was the Loomis Apartments, Boudwin did that; this was for him,” followed by a brief description of its design. (Strangely, another local architect, Russell Mills, also appeared to claim credit for Loomis Manor in a 1952 letter found at the Nevada Historical Society, but that link is less persuasive.)

The longstanding attribution of Loomis Manor to Williams in no way suggests an attempt on anyone’s part to deceive or mislead. Recollections can vary, which is why historians always seek additional corroboration of oral accounts. Indeed, it is entirely possible that while working down the street on a project also connected to Anna Loomis, Williams contributed ideas about the apartments her family was building, either directly to her or to the contractor they shared. But close review of the available evidence indicates that Paul R. Williams was not responsible for the design of Loomis Manor.