Paul Revere Williams in Southern Nevada

Claytee White

“I am an architect. Today I sketched the preliminary plans for a large country house which will be created in one of the most beautiful residential districts in the world, a district of roomy estates, entrancing vistas, and stately mansions. Sometimes I have dreamed of living there. I could afford such a home. But this evening, leaving my office, I returned to my own small, inexpensive home in an unrestricted, comparatively undesirable section of Los Angeles because… I am a Negro.”

Intro

From the early 1940s to the mid-1960s, Paul R. Williams (1894-1980) added architectural beauty and elegance to what was then the geographically barren landscape of Las Vegas. He did this while encountering profound racism, which was not unique to Las Vegas during this era, but that permeated the entire country.

The 1940s mark the beginning of the “Great Migration”[i] of Blacks to Las Vegas that brought numerous men and their families to the region as a result of a growing casino and gambling industry. That migration slowed after a while but never ended. The need to house Black workers is what brought Paul R. Williams to southern Nevada for the first time in 1942. Williams designed the Carver Park Housing development to help house the Black employees of Basic Magnesium Incorporated (BMI), a plant established to process manganese ore to make bullets, planes, and guns during World War II. At the same time, a separate housing development—Victory Village—was designed and constructed by a different architect and developer for white workers. The two adjacent neighborhoods were intentionally divided by what is today, Lake Mead Boulevard.

This was also the city-building era of Las Vegas, a twentieth-century town founded in 1905. The federal government had poured funding into the town in the 1930s to build Boulder Dam (now known as Hoover Dam); constructed the first federal building that housed a post office on the first level and courthouse on the second floor; and in the 1940s, made capital investments for the war effort. These investments encouraged the manufacture of implements of war that would be lighter and more precise. Magnesium caused bullets to shoot straighter, planes to fly faster, and bombs to be more destructive. The federal government commissioned BMI to process the ore that would be used to build this war equipment. The theory behind this technology was already being used in Germany so the U.S. government had to gear up quickly. This plant and federal housing for workers started Basic Township that is now the City of Henderson. Housing for the portion of workers who were Black, brought Paul R. Williams to the Las Vegas area for the first time. He designed Carver Park while Victory Village, the housing for White workers was also being constructed.

[i] The official Great Migration of Blacks fleeing the South began in 1917 and can be documented to the 1970s. See Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of American’s Great Migration. New York: Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc., 2010. Page 8.

Click to Download PDF Version

Paul R. Williams: The Early Years

The story of Paul R. Williams began on February 18, 1894 in Los Angeles. By his fourth birthday, both of his parents had succumbed to tuberculosis; his father died when the young Williams was only two years old. Paul and his brother were sent to different foster homes. Considering this sad beginning, it is heartening that he eventually found a foster family that supported his educational interests. Mr. and Mrs. C.I. Clarkson were not deterred from supporting their son even when a high school teacher rebuked Williams’ desire to become an architect. There are several versions of the white teacher’s response, but to paraphrase, the teacher asked: “Who ever heard of a Negro architect?”

It is hard to believe that Williams persevered, overcame the racial bias of his teacher and of that era, and became not only the first Black architect member of the American Institute of Architects, but also a designer of almost 3,000 structures, including homes for luminaries living in Los Angeles and Hollywood.[i] Williams studied at The Los Angeles School of Art and Design, the Los Angeles branch of the New York Beaux-Arts Institute of Design Atelier, and designed his own course of study at the University of Southern California. His professional work began with the firms of Wilbur Cook, Jr., a landscape designer, and Reginald Davis Johnson who designed luxury homes. “The first thing Johnson did was put me on a $100,000 house…,” Williams later explained. “I’d never been in a house that cost more than $10,000. I couldn’t guess how a person could spend that much money. I soon found out.”

Paul Revere Williams and Della Mae Givens married in 1917. This union too, was one that supported his dreams, giving him the freedom to flourish and create. He designed his first ten luxury homes in Flintridge, California. By 1921, as he was making inroads in his field, he was appointed to the Los Angeles Planning Commission, helping to make strategic plans for the city where he was designing homes and municipal buildings. In 1922, Williams opened his own architectural and design firm in Los Angeles and would awaken to the extent of his limitless talent.

His firm flourished in the Roaring Twenties just as entertainment, jazz, and the arts were amplified in cities throughout the country. Williams expressed art through his architectural design leading the way with both small, affordable houses for first-time homeowners and more spacious, historic revival-style homes for wealthier clients. The larger homes made the affluent residents of Beverly Hills, Hancock Park, and Windsor Square’s take notice. Movie stars and businessmen contracted for his homes and landmark buildings included Saks Fifth Avenue, Golden State Mutual Life Insurance, and the MCA building. The twenties ended with the crash of the stock market in 1929, but Williams’ business remained strong, even though some projects were downsized.[ii] His design philosophy was simple and it worked in depression-proof Hollywood, “know when to quit…People don’t always know what they want. It is the architect’s job to help them find it and keep within the bounds of grace.”[iii] As World War II approached, he and most of his staff chose war work so Williams closed his practice and supported the military’s housing efforts.

[i] PRW designed homes lived in by Frank Sinatra, Lucille Ball, Desi Arnaz, Lon Chaney, Barbara Stanwyck, Bill Cosby, Denzel Washington, Tyrone Powell, Betty Grable, Harry James, and many others.

[ii] https://www.kcet.org/shows/hollywoods-architect-the-paul-r-williams-story/visual-timeline-the-remarkable-life-of-paul-revere-williams. The Remarkable Life of Paul Revere Williams by the Paul R. Williams Project, 5 February 2020. See timeline section 1929 of Visual Timeline:

[iii] https://www.kcet.org/shows/hollywoods-architect-the-paul-r-williams-story/visual-timeline-the-remarkable-life-of-paul-revere-williams. The Remarkable Life of Paul Revere Williams by the Paul R. Williams Project, 5 February 2020. See timeline section 1930 of Visual Timeline:

War Work in Las Vegas

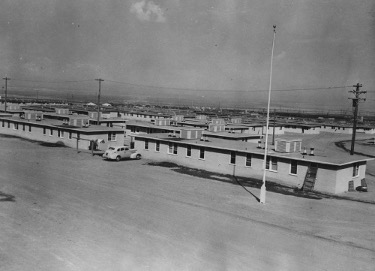

Federal government “war work” brought Williams to Las Vegas. The housing he designed southeast of the City of Las Vegas offered a refuge for Black workers escaping the South to a place that was known as “Basic Townsite,” where they found employment at Basic Magnesium Incorporated (BMI). (The townsite eventually became known as Henderson, Nevada, which is the second largest city in Nevada today.) Workers at BMI were both Black and White, and given that Southern Nevada operated as a segregated community at the time, this required two separate housing areas: Carver Park for Black African Americans and Victory Village for Whites. Williams designed the Carver Park complex, which opened in 1943 with sixty-four (64) units for single male workers, one hundred and four one-hundred and four (104) bedroom units, one hundred and four (104) two-bedroom units, and fifty-two (52) three-bedroom apartments. The complex also included a school, recreation hall, and a building that became the Elks Lodge.

The modern design of Carver Park was low slung with curved edges that bespoke a raw elegance unlike the houses in the South that many Black left behind. The modest L-shaped, single-story buildings had side-gable roofs that were nearly flat with overhanging, boxed eaves. Unfortunately, by the time Carver Park opened, most Black workers had already settled just west of the tracks near downtown Las Vegas in area called the Westside. Beginning in the 1930s it had become known as a Black American neighborhood where soul food, the blues, dance, black barber shops and beauty salons, and black churches marked home. Although the Carver Park development, mandated by the federal government as temporary housing, was razed, one building, the Elks Lodge still stands in 2022. The frame and stucco constructed buildings of Carver Park were removed between 1980 and 1990.[i] Williams, in the coming decade, would leave his mark on the Westside as he had on Basic Townsite.

The Westside is one-half mile from the original town of Las Vegas, which was founded by the San Pedro, Los Angeles, & Salt Lake Railroad as a watering and railroad repair site in 1905. Blacks moved west across the tracks in the early 1930s as all residents moved out of the town’s core. Whites moved eastward into new neighborhoods, some that enforced restrictive covenants. City government officials led by Mayor Ernie Cragin required that Blacks move westward across the tracks if they wanted to renew business licenses as downtown made way for increased commerce. Additionally, the designated Black area, Block 17, was needed for the first federal building. Construction on a post office with courthouse on the second level began in 1931. The area west of the tracks became a hub for residents, businesses, churches, and schools and sustained a rapidly growing Black community. Blacks moved to the Westside and began to build homes and focused inwardly on social and economic gains to advance the idea of a better life that had brought them to Las Vegas initially.

During the 1940s, the City of Las Vegas re-envisioned itself as an urban area that would insure its unparalleled uniqueness. The strategy proved successful and led Las Vegas to become the entertainment capital of the world. The fledgling city began its maturation by modernizing its government, electing a mayor with a vision, and hiring a well-qualified city manager. Urbanization quickly accelerated with the development of the Las Vegas Strip—a popular street along which casinos, hotels, and entertainment venues thrived. In the same way that Williams had been brought in to develop Carver Park, California businessmen claimed the initial design of Strip development with the El Rancho, the Last Frontier, the Flamingo, and the Thunderbird Hotel Casinos. Paul R. Williams would contribute his own blueprinted vision to the City of Las Vegas by adding a building at the racetrack; a hotel, two motels, and a cathedral to the Strip, and housing to the Westside.

Paul Williams’ designs commenced, simultaneously in mid-1950, as the first integrated hotel casino, the Moulin Rouge, was under construction having been designed by local architects Walter Zick and Harris Sharp. Williams created both the Berkley Square housing development on the Westside near the Rouge and the Royal Nevada Hotel Casino on the Strip. The Moulin Rouge and the Royal Nevada shared the fate of being caught up in an economic downturn, both enjoyed a very short heyday period. First though, the long-forgotten racetrack graced the City of Las Vegas.

[i]

Carver Park

Carver Park, 1943A Racetrack for Las Vegas

One of Williams’ first design projects in Las Vegas was a major thoroughbred horse racing facility he designed for New York promoter and entrepreneur Joseph Smoot. In 1947, Smoot hitched a ride with Hank Greenspun (the eventual founding publisher of the Las Vegas Sun) on a cross country road trip, where he hatched a plan for a major horse racing complex called Las Vegas Park. He sold his dream to thousands who invested $2 million in the scheme. To sell the idea, in 1950, he hired architects Arthur Froehlich and Paul R. Williams for the cachet and credibility they would bring to the project. They drew pure elegance with graceful lines intersecting with slanting angles that captured “the spirit and future of Las Vegas as a pace setter throughout the world.”[i] But even their elegant Jockey Club could not help Smoot’s scheme. Eventually Smoot was charged with felony embezzlement and a trustee was appointed by Judge Roger Foley to run the track. The opening day crowd of 8,000 soon dwindled. The 60-day racing season lasted for 13 days.[ii] The property was eventually sold to Joe W. Brown, a wealthy oilman, and over the years the property became a portion of three Las Vegas iconic treasures: the Las Vegas International Country Club and Golf Course, the International Hotel (Westgate), and the Las Vegas Convention Center. Although the Las Vegas Park Racetrack was short-lived, Paul R. Williams’ next project, Berkley Square proved to be a more lasting development.

[i] Las Vegas Park, Las Vegas NV, A Man and His Work, https://www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/gallery/paul-r-williams-and-arthur-e-froelich/

[ii] A Sad Saga: Horse Racing in Las Vegas, Las Vegas Sun, Tuesday, April 29, 2008 and Gallery: Las Vegas Park, Las Vegas, NV https://www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/gallery/paul-r-williams-and-arthur-e-froelich/

Horse Race Track in Vegas

Las Vegas Park Horse Racing Track Jockey Club, 1947Berkley Square

Berkley Square was the first Black housing development in Las Vegas. Paul Williams used his concept of the small house movement to construct 148 homes using his Contemporary Ranch style design. He integrated two models that varied by roof type, porch overhang, façade finishes, and fenestration. The small house movement was an innovative way to lower construction costs around the end of World War I with a redefinition of the ideal floorplan for the new lifestyles of the ideal American family. No more than six rooms in a variety of styles – bungalow, Colonial, Spanish, and others - Williams added the idea of bringing in outdoor livable space sometimes with an outdoor fireplace. The Berkley Square area contained broad streets with sidewalks separated from the street with a planting strip. Homes were set back from the street with lush front lawns and an open car port attached to the homes. All were one-story with a low-pitched, gabled or hipped roof with wide eaves; an open-interior plan blending functional spaces; strong connections to the outside; with informal or rustic materials or details; and a plan that is rambling and suggestive of wings or additions.[i]

There are still several questions that surround this project that opened for occupancy in 1954 but designed by Williams in 1949 with the original name of Westside Park. For instance: How did the development secure FHA funding at a time when there were no fair lending practices for Black home ownership until the Fair Housing Act of 1968? Did the team’s combined celebrity touch someone in Washington, D.C.? Edward A. Freeman and J.J. Byrnes of Los Angeles financed the project. Did the later-added financier Thomas L. Berkley, attorney, media owner, developer, civil rights advocate know Paul R. Williams? The developer was Leonard A. Wilson of Las Vegas. Construction was supervised by Harry L. Wyatt of the Las Vegas firm Burke and Wyatt. Massie L. Kennard, a Las Vegas civil rights leader, was the real estate agent.[ii] How did all these forces align? And finally, why do houses in Highland Square, a few blocks away from Berkley Square look identical?

Esther Langston, one of the first Black professors at the University of Nevada Las Vegas (UNLV) lived in the development as soon as it opened. She talked about how it was the personification of community. Her husband, an airman at Nellis Air Force Base and other men in the community would make sure that they cut the grass and trimmed the lawns of any serviceman who was away on out-of-town duty. And though, this place was the epitome of neighborliness, Paul Williams found that Las Vegas “wasn’t as friendly’ as Southern California or cities back East where he also did business. When he was in Las Vegas or Reno, there was no place he could stay; couldn’t stay in hotels or eat in restaurants.” Where did he stay while working on projects in Las Vegas?

[i] NR Historic Register Application – Berkley Square; United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. section number 7, page 3.

[ii] Berkley Square Neighborhood on National Historic Register. Las Vegas Sun Newspaper by Dave Toplikar, Friday, November 20, 2009.

Berkley Square

Berkley Square, 1954-1955Designing for the Strip: Royal Nevada, Las Concha Motel, El Morocco, and a Cathedral

While working on the racetrack and Berkley Square, Williams received another commission, this time for a casino resort known as the Royal Nevada. Businessman Frank Fishman who already owned hotels in California and Texas, wanted to expand into the Las Vegas gaming industry. He invited Williams along with California architect John Replogle, to design the Royal Nevada Resort and Casino. Construction began in 1954, at the same time Berkley Square was being constructed. Williams also designed the large, jeweled crown, which was fabricated by the Young Electric Sign Company (YESCO), and that sat atop the main building. The Royal Nevada Resort and Casino opened in 1955 but faced financial problems from the beginning, closing only a year later before it was absorbed by owners of the adjacent Stardust Hotel.

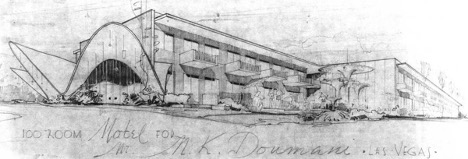

The decade ended for Williams with another edifice on the Strip, the La Concha. This iconic motel was designed for housing and food only, no gaming. The timing was perfect because hotel rooms were scarce. The Doumani family, however, wanted more than a typical motel. M.K. Doumani came to Las Vegas from California in 1961 and bought land to build the La Concha as an upscale resort across the street from the Riviera Hotel & Casino. It was Edward Doumani a 1960 USC graduate who invited Paul R. Williams to design the building.

Today, the La Concha is noted as Williams’ most iconic structure in Nevada, known for its intersecting hyperbolic paraboloid lobby made from glass and concrete. The graceful curvilinear forms of the structure echo the details—such as arched entries, staircases, and ceilings—of the residences Williams designed in Southern California. Often described as an example of Googie-style architecture, inspired by the sleek futurism of the Space Age and Atomic Age, the La Concha Motel became a favorite destination of the rich and famous, including Elizabeth Taylor, Ronald Reagan, Wayne Newton, Elvis, Ann-Margret, Flip Wilson, and the Carpenters.

The imposingly stunning 1,100 square-foot lobby welcomed visitors to a 100-room motel with the unforgettable style and intimacy beyond that of the larger hotels. Was the building a stylized conch shell, a butterfly, or something from science fiction? It is also described as “the most beautiful thing ever seen on the Strip” or “I fell in love with the building” of “It’s insanely gorgeous.” This famous motel lobby was disassembled in 2006 and relocated from the Strip to South Las Vegas Boulevard, where in 2022, it is still being used as the entry to the Neon Museum.

Another casino attributed more recently to Williams, and also associated with the Doumani Family, is the EL Morocco, which opened to the public in 1964. The design for the El Morocco was as graceful as the La Concha, which was located just next door on the Strip. The circular lobby of the El Morocco was typical of the stylized architecture of the era, each room had its own private balcony, and the pool was award winning. When reached recently by email, a member of the Doumani family, Lorenzo Doumani, confirmed that, “Paul Williams did indeed design the El Morocco in the early 1960s for my family.” The Doumani family plans to open a new resort in Las Vegas in 2023, that will take its inspiration from the design of Williams’ La Concha Motel.

St. Viator’s Guardian Angel Shrine

In 1961, Paul R. Williams also designed his first house of worship in Southern Nevada after several spiritual structures in Los Angeles. Today, sixty-one years later, The Guardian Angel Cathedral still stands beautifully on the Las Vegas Strip.

After designing buildings on the Las Vegas Strip for nearly a decade, Williams was asked by Moe Dalitz of United Resort Hotels, to design a new Catholic Church, which was originally known as St. Viator’s Angel Shrine. There had long been a desire to build a church near the strip to serve the needs of hospitality workers. A Jewish businessman known for his association with organized crime syndicates, Dalitz donated the land and underwrote the construction of the church in a move that was seen by many as an attempt to clean up his image. When the church opened in 1963 as the Guardian Angel Shrine, Williams’ A-frame structure was celebrated as modern masterpiece that could seat over 1,000 congregants. With mosaic work and stained glass designed by Edith Piczek and Isabel Piczek installed in the twelve triangular recesses bisecting the A frame, in a rather unique fashion. Each window illustrates a Station of the Cross with gambling themes illustrating the story. The structure underwent a $1.5 million renovation in 1995, attesting to the building’s important architecture today. The church that holds its own against the glitz, glamour, and neon of the Strip is known as the Guardian Angel Cathedral.

Royal Nevada Hotel Casino

Royal Nevada Hotel Casino, 1954

La Concha Motel

La Concha Motel, front lobby view, 1961

La Concha Motel

La Concha, side view, 1961

El Morocco Motel

El Morocco Motel, 1961

Guardian Angel Cathedral

Guardian Angel Cathedral commissioned by Moe Dalitz, a Jewish casino mogul, 1963The Skylift Magi-Cab

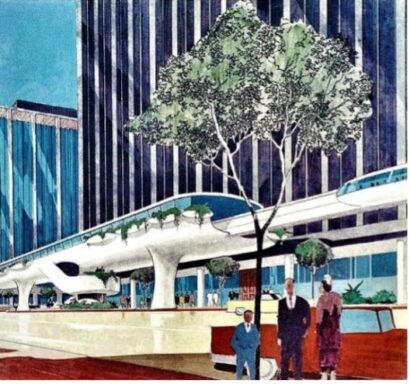

Williams’s final proposal for Las Vegas never materialized—except for on paper. The Skylift Magi-Cab was intended as a 15-station monorail system to transport tourists from downtown Las Vegas to McCarran Airport (now known as Harry Reid International Airport). Lockheed and Guerdon Industries turned to Paul Williams for this commission, because, as had been the case with past commissions, WIlliams reputation offered a certain cache, that special savoir faire, to allow the images’ future possibilities to shine through vividly while on paper. Williams proposed a futuristic monorail that has been described as having a “post-Sputnik-Moderne style.”

Williams design was popular, but the Skylift was never constructed. Local historian Dorothy Wright speculated that, “Although the monorail was touted as providing as much flexibility as the automobile, this imaginative mass transit project may have been doomed by American’s devotion to their single-family cars.”[i] While Williams’ design proposal captivated leaders and planners at city hall, and could have been constructed without public funds, the popularity of the automobile appears to have won out over this sleek, space-age mode of transportation for the future.

I end with a return to the mysterious. There are mysteries that I mentioned previously – what about Highland Square with homes that look exactly like those in Berkley Square? We have decided that it is ripe for investigation and with the same developers, will probably be listed as an official historic community adding to the list of Paul R. Williams’ neighborhoods in southern Nevada. With that solved - where did Paul Williams reside while in Las Vegas prior to integration? Yes, there were boarding houses in the Black community. We know that Sammy Davis, Nat King Cole, and Pearl Bailey, among many other notables, lived in these locations and became part of the local Black community during their engagements that lasted weeks at a time. But we have never heard of or read about the presence of Paul Revere Williams as a guest in the Black community. This architect achieved more than most in his field on the worldwide stage. He taught himself to draft detailed images of homes and business structures upside down because he could not sit beside his white clients. Which Westside boarding house was privileged with Paul Revere Williams’ presence and stories and friendship while he created beauty in Las Vegas?

Paul R. Williams was a man who lived in courage, was alive in his creative energy, and rose beyond the systemic employment racism of his era. While he encountered discrimination and was hurt by it, he decided to stand firmly in his craft, allowing his work to speak for him. In Las Vegas that work included Carver Park, The Jockey Club at the Horse Racing Track, Berkley Square, The Royal Nevada Hotel Casino, the La Concha Motel, El Morocco Motel, Guardian Angel Cathedral, and the Skylift Magi-Cab. Williams was an artist, an engineer, an architect, a genius.

Obstacles in the life of Paul R. Williams may have been great but nothing could extinguish his brilliant flame. After his death, he was awarded the Gold Medal, the AIA’s highest honor and was inducted into the Institute’s College of Fellows. “Without having the wish to ‘show them.’ I developed a fierce desire to “show myself.’ And along the way, he showed the world.

[i] The PRW Project: https://www.paulrwilliamsproject.org/gallery/skylift-magi-cab-las-vegas-nevada/

Skylift Magi-Cab

Skylift Magi-Cab, 1966